Changes to UK Competition and Consumer Enforcement in 2025: What You Need to Know

December 18, 2024

The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers (DMCC) Act is set to come into force on 1 January 2025, marking a significant milestone in the evolution of UK competition and consumer enforcement.

This landmark legislation strengthens the powers of the Competition and Markets Authority, expanding its jurisdiction over global mergers, enabling it to regulate tech giants, and empowering it to impose substantial fines for breaches of consumer law. These changes are far-reaching and may affect any business with a presence in the UK. To help you navigate these changes, we have summarised the most important provisions of the DMCC Act.

New Digital Markets Regime

Firms with Strategic Market Status

- Applies to companies with global turnover >£25 billion or UK turnover of >£1 billion.

- The CMA can designate these firms as having strategic market status (SMS) if they have (i) substantial and entrenched market power, and (ii) a position of strategic significance, both in respect of a digital activity linked to the UK.

- Digital activities include providing a service through the internet, providing digital content, or any activity carried out for those purposes.

- The UK nexus condition is satisfied if the digital activity has a significant number of UK users, the firm carries on business in the UK in relation to the activity, or the activity is likely to an immediate, substantial, and foreseeable effect on trade in the UK.

- The assessment of substantial and entrenched market power is forward-looking over a period of at least five years.

- A firm will have a position of strategic significance if one of four possible conditions is met: (i) the firm has achieved significant size or scale in respect of the digital activity, (ii) a significant number of other firms use the digital activity in carrying on their business, (iii) the firm’s position in respect of the digital activity would allow it to extend its market power to a range of other activities, or (iv) the firm’s position in respect of the digital activity allows it to determine or substantially influence the ways in which other firms conduct themselves, in respect of the digital activity or otherwise.

- SMS investigations will last up to nine months, and the CMA must consult publicly before designating a firm.

- SMS designations will be reviewed at least once every five years.

SMS Conduct Requirements

- The CMA can impose conduct requirements on an SMS firm to achieve any of the following objectives: fair dealing, open choices, and trust and transparency.

- Unlike under the European Commission’s DMA regime, the CMA will impose firm-specific conduct requirements drawn from the permitted types set out in the legislation. The permitted types are broadly framed, e.g., trading on fair and reasonable terms and not restricting interoperability.

- The DMU will also develop firm-specific guidance to explain how conduct requirements apply.

- The CMA may impose conduct requirements on any part of an SMS firm’s business, not just the relevant digital activity. The aim is to prevent the SMS firm from carrying out non-designated activities in a way likely to reinforce its market power or position of strategic significance.

- Conduct requirements must be proportionate, meaning they must be effective, no more onerous than necessary to achieve their intended aim, and not produce disadvantages that are disproportionate to their aim.

- The CMA must consider consumer benefits before imposing conduct requirements.

- The CMA may also accept commitments relating to a conduct requirement from any SMS firm subject to a conduct investigation. The CMA will typically stop investigating any conduct to which a commitment relates.

SMS Pro-Competition Interventions

- The CMA can impose pro-competition interventions (PCIs) on any part of an SMS firm’s business to address adverse effects on competition (AECs).

- An AEC arises when a factor related to the relevant digital activity prevents, restricts, or distorts competition in connection with that activity.

- The CMA will assess an AEC against a range of indicators, including whether (i) the SMS firm’s profits are reasonable, (ii) its competitive position is based on merit, and (iii) its customers can switch between providers.

- The CMA can implement a PCI in two ways: through a pro-competition order (PCO) or by making non-binding recommendations to another public body. In appropriate cases, the CMA may also accept commitments from the SMS firm to remedy, mitigate, or prevent the AEC or the detrimental effect on UK customers.

- The CMA will use PCIs to remedy, mitigate, or prevent AECs. It has broad discretion in its choice of remedies, including behavioural (e.g., access and interoperability requirements) and structural (e.g., divestment) remedies.

- Before imposing a PCI, the CMA may consider any benefits to UK users resulting from the factors giving rise to the AEC. SMS firms should submit any evidence supporting these benefits early in the process.

- The CMA may require an SMS firm to test and trial different remedy design options before imposing any PCI on an enduring basis.

- A PCI must be proportionate, meaning it must be effective, no more onerous than necessary to achieve its intended aim, and not produce disadvantages disproportionate to its intended purpose.

Mandatory reporting requirement for SMS firms

- SMS firms must report any deal involving a target with a UK nexus (or a joint venture expected to have a UK nexus) if (i) the SMS firm acquires a shareholding or voting rights that cross the 15%, 25%, or 50% threshold, and (ii) the total consideration is at least £25 million. The SMS firm must submit a report each time a threshold is crossed.

- Reports must be submitted before the deal completes.

- The CMA has 5 working days to confirm whether the report is sufficient (the ‘review period’) and a further five working days to review the deal (the ‘waiting period’). Unless the CMA gives its consent, SMS acquirers must wait for these periods to end before closing the deal.

Changes to Merger Control

New Jurisdictional Thresholds and Procedural Changes

- The CMA’s ‘turnover threshold’ for reviewing mergers has increased from £70m to £100m.

- There is a new jurisdictional ‘safe harbour’ – the CMA will have no jurisdiction over a deal if no party has more than £10 million UK turnover.

- The CMA can now review some purely vertical and conglomerate deals, even where the target has little or no revenue in the UK. Under the new test, the CMA has jurisdiction to review any deal where one party – usually the acquirer – has UK turnover of more than £350 million and a share of supply of at least 33% in any UK goods of services, provided the other party – usually the target – is active in the UK.

- Merger parties can now ask the CMA to fast-track their case to a Phase 2 investigation without having to concede that it may give rise to competition concerns. In these cases, the CMA may extend its Phase 2 review period by up to 11 weeks, rather than the usual 8 weeks, if there are special reasons.

- The CMA will have new powers to fine companies for breaching undertakings given at phase 1 or phase 2 and enforcement orders (including final orders and compliance orders).

Changes to Consumer Law

New Consumer Protection Powers (expected April 2025).

- The CMA can now enforce consumer protection laws directly without court proceedings, and it can impose fines of up to 10% of a company’s global turnover for breaches.

- The CMA has the power to impose penalties for administrative breaches, such as failure to comply with requests for information.

- Parties can appeal adverse decisions to the High Court within 60 days (though some administrative breach decisions need to be appealed within 28 days).

- The CMA now also has the power to impose Enhanced Consumer Measures, which previously required a court order. These include redress measures, such as compensating consumers who suffer a loss; compliance measures, such as improved business practices to reduce the risk of infringing conduct occurring in future (e.g., better training and guidance); and choice measures, such as providing consumers with better information to help them choose more effectively between different suppliers.

- Fake reviews are now ‘blacklisted’ under Schedule 1 of the CPRs. The Act prohibits businesses from submitting or commissioning fake consumer reviews, and for not taking reasonable and proportionate steps to prevent the publication or removal of such reviews.

- Businesses offering subscription contracts have new duties to provide clear information before consumers sign up, send reminder notices before a free trial or low-cost offer comes to an end (and at six monthly intervals thereafter), and facilitate straightforward termination processes (including “cooling off” periods).

- Drip pricing is now also an automatically unfair practice. New rules to address drip pricing requiring the headline price to include all mandatory charges that the customer will incur if they make a purchase. If any mandatory component cannot be calculated in advance, businesses must disclose the existence of these additional charges and how they will be calculated.

Changes to Antitrust

Antitrust, Dawn Raids, and Information Gathering Powers

- The UK’s prohibition on anticompetitive agreements now applies to agreements implemented outside of the UK, where there are (or are likely to be) direct, substantial, and foreseeable effects within the UK.

- There is a new duty for companies and individuals to preserve documents where they know or suspect that an anti-trust investigation by the CMA is being (or is likely to be) carried out.

- The CMA’s new dawn raid powers allow it to search all documents accessible from the premises when searching under warrant, even those stored offsite or offshore, and it may operate any equipment found on the premises for the purposes of accessing such information.

- Inspectors can now require parties other than those under investigation (e.g. customers, suppliers or competitors) to respond to questions or produce documents.

- The CMA now also has the power to seize and sift documents found during raids on domestic as well as business premises.

- There are increased penalties for non-compliance with information gathering and other requirements imposed during a CMA investigation.

Changes to Competition Litigation

New Powers for the CAT and the Courts

- The CAT will review decisions made by the CMA – including SMS designation decisions, conduct requirements, or pro-competition interventions – on a judicial review basis. A full merits review will apply to appeals against fining decisions under the DMCC.

- The CAT now has new powers to:

- Grant declaratory relief. Claimants can now apply to the CAT for a declaration about the lawfulness of an agreement or conduct without needing to seek an injunction or claim damages.

- Award exemplary damages. Courts and the CAT can now award exemplary (i.e., “punitive”) damages in private competition claims. Exemplary damages are typically awarded where compensatory damages are considered insufficient in light of the defendant’s egregious conduct. Exemplary damages will not be available in collective proceedings. Immunity recipients will be liable to pay exemplary damages to their direct or indirect customers or suppliers, but they will not be liable for exemplary damages that the claimant is unable to recover from other parties.

- Separately, those suffering loss/damage from the conduct of an SMS firm may bring standalone or follow-on claims to the CAT:

- Standalone claims include civil claims for damages, injunctions, and other relief. Standalone DMCC claims differ from typical standalone competition claims, which can be brought without any prior action by a competition authority. Under the DMCC, a standalone claim requires the CMA first to have imposed obligations on the SMS firm, such as a conduct requirement or a pro-competition intervention, which can then be the subject of a claim for an alleged breach.

- Follow-on claims can be brought following a CMA decision finding a breach by an SMS firm of a conduct requirement, pro-competition intervention, or a requirement to comply with commitments, but not on an opt-out collective basis.

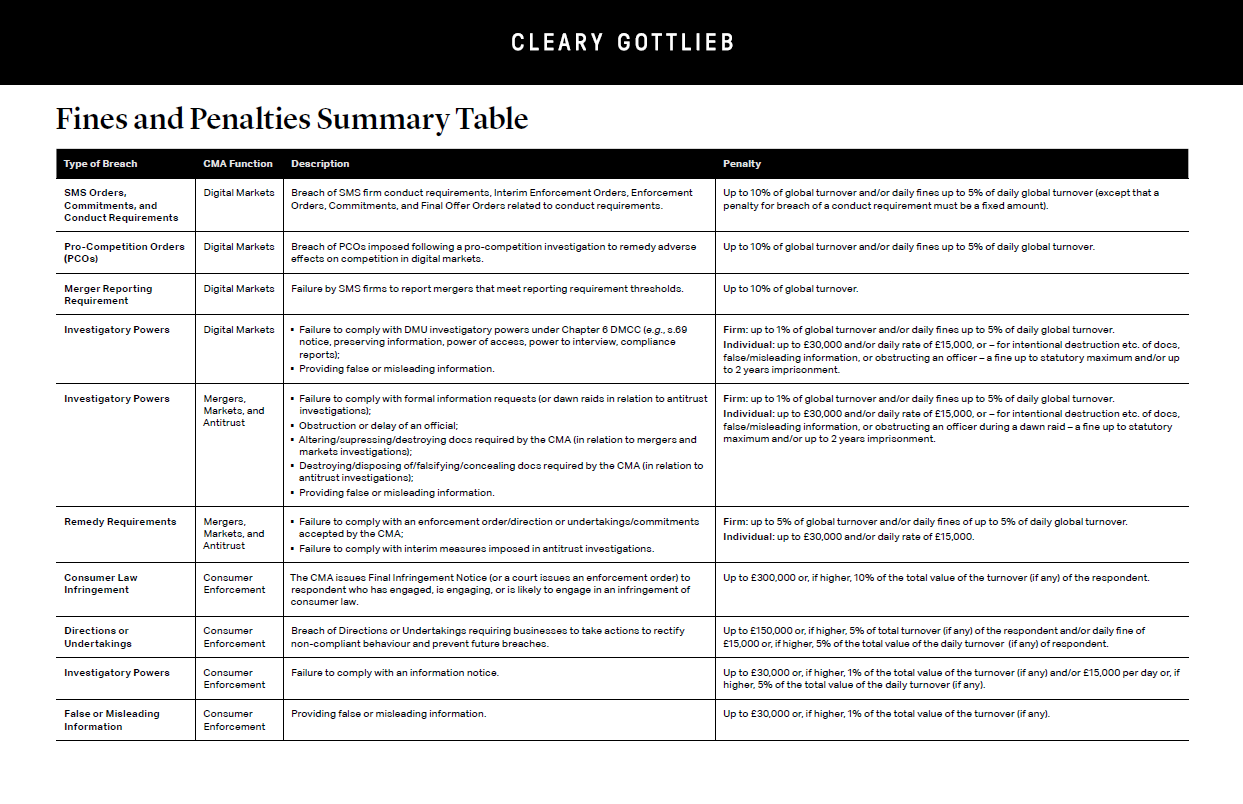

Fines and Penalties Summary Table